Bruce Lee’s Lasting Impact on Asian American Identity

An Interview With Jeff Chang

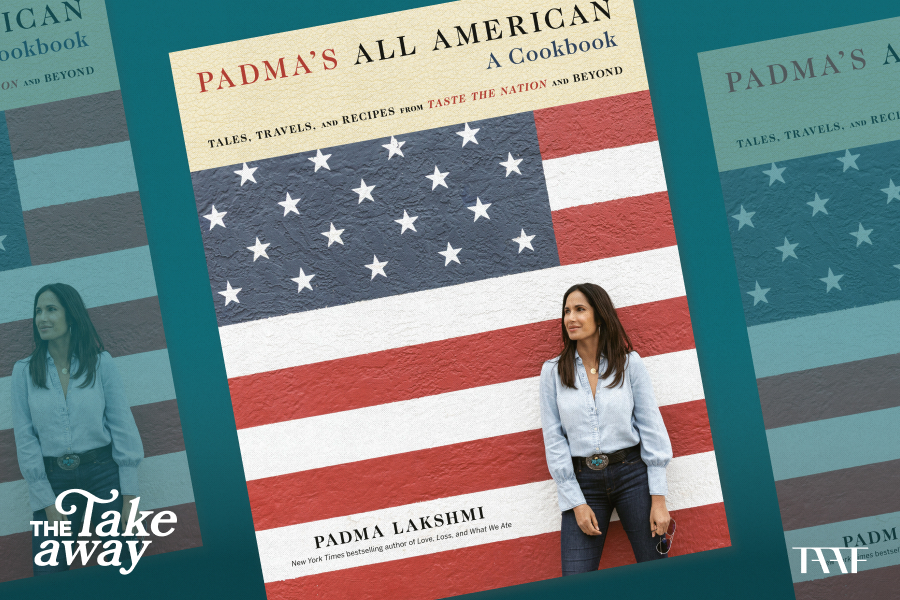

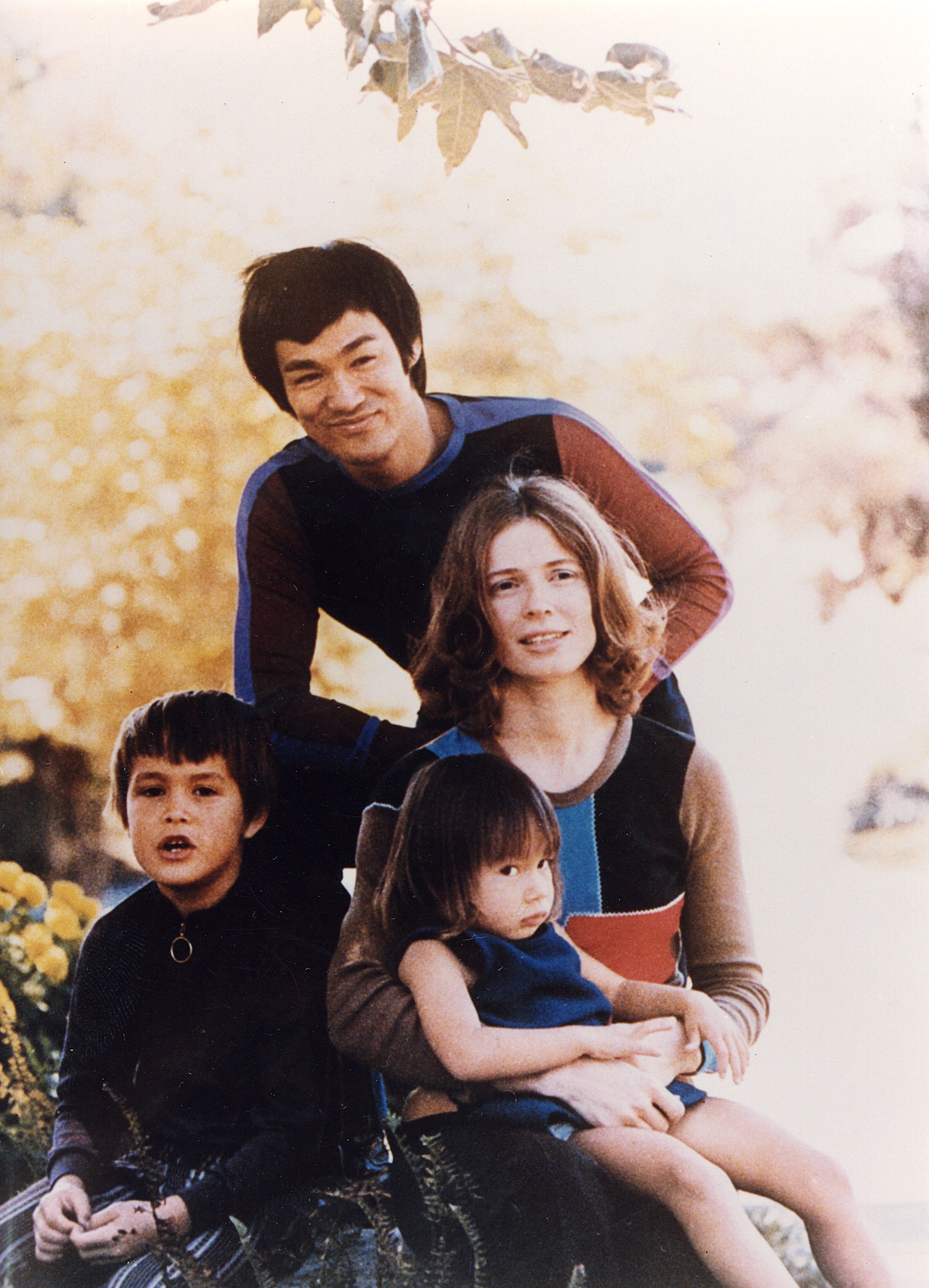

In Water Mirror Echo: Bruce Lee and the Making of Asian America, author Jeff Chang looks beyond Bruce Lee’s legacy as a martial artist and star of TV and film, uncovering the social and political circumstances that shaped who he was, and how he in turn shaped the concept of an Asian American identity.

The book is both a deeply researched cultural history and an incredibly intimate portrait of a man who was more than just an action hero. Water Mirror Echo explores the many other sides to Bruce Lee, from his friendships, ambitions, and loves to his philosophical beliefs. I caught up with Jeff Chang to get insight into the missing pieces of Bruce Lee’s story, Asian representation in Hollywood, and the connections between Asian American activism and the collective struggle for liberation.

Why was it important to you to write this book? How did you want to approach Bruce Lee's story that was different from previous biographies?

An Asian American editor came to me back when there weren't too many Asian American editors in the business, and said, “Hey, you did this book on hip-hop. Could you do something on Bruce Lee for me?” And it took me about 30 seconds to say yes, because Bruce is the most famous Asian American who's ever lived. At the time, I thought that I would want to do it just because I was such a huge Bruce Lee fan. And, of course, I was coming from a background with an Asian American Studies degree, having a deep interest in Asian American history and in the history of Asia and the Pacific in general. And having really close friends and writing heroes of mine who’ve helped us to rethink the way that we understand histories of Asia and the Pacific––people like Viet Thanh Nguyen, or any number of my mentors that have been transforming the way that we think about Asian America––I wanted to bring that perspective to writing this. But it really crystallized during the pandemic. I had been mentoring a lot of folks. I was teaching when I was at Stanford, and I think for young folks at that particular time, it was really this question of, what even is an Asian American, how do I relate? It wasn't necessarily the sense of shared struggle that folks might have had back in the '60s and the '70s. And so there was this entropy to the whole notion of Asian American.

So there was sort of a generation gap, but the pandemic happens, and then suddenly there's all of this energy to reassert this idea of, if not a unified Asian America, at least the idea of Asian America. Thinking about Bruce and martial arts in that particular context was a completely different way to begin to approach it. During that particular period, the image of Bruce is jumping back up. He's up on our feeds. Murals are going up in Oakland, San Francisco, and Los Angeles, all around the country. And at that particular point, I felt a little bit more confident to be able to lean into the “Asian Americanness” of Bruce.

You discuss the creation of the term “Asian American” and Asian American activism in the context of the Black Power movement. Was it an intersectional movement?

Yeah, it was always intertwined with it. It was inspired directly by the Civil Rights Movement. [Bruce] talked to a lot of the folks who were there, literally in the room. I talked to a lot of Bruce's contemporaries. First of all, Asian Americans are living with Blacks and Latinos and Native Americans and poor whites in places like the Central District in Seattle. So that's one thing that's maybe hard for folks now to be able to understand. They're living in segregated neighborhoods, living on top of one another. The dojo in Seattle is across the street from the projects where Black folks were living…and so when the Civil Rights Movement jumps off, it's not far away, it's really immediate. Bruce is sitting with these folks who are talking about this kind of stuff every day. He’s hanging out at Garfield High School, where Martin Luther King goes to speak. It's a central node for the Black community. Garfield High is one of the central places where the Black Panther Party is meeting. So that gives you a sense spatially of what that's like.

It's not just the intimacy, but it's the example that inspires Asian American activists to become civil rights activists. And to adopt a lot of the language. I think what happens in the Bay Area is because of the rise of the anti-war movement there very early on, those two threads intersect, and that gives a new language to young Asians in the Bay Area, particularly around Berkeley, around San Francisco State, College of San Mateo—the college campuses. To be able to say: “Hey, what's going on here? The anti-war movement is about fighting these wars and bringing the boys home from Asia. But what about all the folks who look like us who are getting bombed?” And the only people who are articulating an alternative to that are people like the Black Panthers. Specifically an anti-imperialist, anti-colonialist point of view, because they're inspired by folks like Ho Chi Minh and Mao Zedong, Gandhi…the anti-colonial movements in Asia. They're relating that to the anti-colonial movements in Africa. So, there's a language there that begins to open up these possibilities, and that's where the idea of Asian America comes from originally.

Was there anything that really surprised you to learn as you were researching this book, that you didn't know about Bruce Lee already?

There are a lot of books out there on Bruce, but there are really not a lot of Asian Americans who are quoted. Bruce came in, as many immigrants do, into networks of other Asians. He was literally dropped into an Asian American context, the moment he got off the ship. This is where all of his closest friends were. So, why aren't we hearing from those folks? Part of the book was about asking, what's that context that Bruce is living in? Why is it the stuff that I've learned about through oral histories and through all the research that's been done in Asia America—why is Bruce not portrayed in that environment? This is not a critique of all the books, but a lot of the ways that we picture Bruce: Bruce at the University of Washington, Bruce in his martial arts classes, Bruce on TV, and, of course, Bruce in the movies later on. But what was his home life like? What was life like on a day to day type of basis? Who are the people who nurtured him? What were his dating habits?

I found that whole section so fascinating. I didn't know he was a dance instructor before he was teaching martial arts. Such an interesting side to read about.

I still haven't found out if he went bowling…but I could probably find that out now that I know these people! I reached out to one of my really good friends [in Seattle]…and I was handed literally from person to person to person in Seattle and San Francisco, and even Los Angeles. It turns out I was apparently always within 2 or 3 degrees. And all these folks were saying, “Nobody's asked me these questions. They always want to ask me about Bruce, but they never asked me these questions about Bruce.” There was this entire cohort of folks that were around Bruce, that had taken care of him, that he had interacted with. So recreating that world was a lot of fun.

This is a very hypothetical question, but had there been no Bruce Lee, what do you think Asian representation in Hollywood would have been like? Were there other people close to making it big? Would it have taken a different course?

It's a great counterfactual, right? There's been a resurgence of interest in Anna May Wong in recent years. And in particular, Katie Gee Salisbury's book, Not Your China Doll, came out as I was close to the end of writing this. Katie was like a kindred soul in that she was trying to find out the same kinds of things that I was trying to find out about Bruce. So we've been able to be in this amazing dialogue over the last couple of years about it all. And the thing that strikes us is that these were two people who were completely outside of the box. They were one of one. There'll never be another Anna May Wong. There'll never be another Bruce Lee. There were of course, a lot of actors in Hollywood, folks who were trying to make it. I got to talk to George Takei. I was lucky enough to be able to stumble upon files of people––Frank Chin interviewing Keye Luke. That was mind blowing.

But it wasn't just their circumstances, it was that they were uniquely determined to break through and break in. And they were also uniquely able to deal with the very intense tides that were pushing against them. To be able to emerge on top of it. And so, no, I think we would have waited. The thing about both of those people is that they had main character energy…the roles that they demanded and the way that they dealt with the spotlight, they were just unique. The saddest part, of course, is that it's still taken us three generations to be able to get to the point that we're at now. And in the moment that we're in, I worry.

In the last chapter, you mention some of the historic achievements in the early 2020s, and how they were, in part, concessions by the industry—the right thing happening for the wrong reasons. Can that all just disappear again?

Yeah, the way that I kind of calm myself down is to know that my sons are in their mid and late 20s, and their generation and a lot of the folks that I mentor are in there fighting the fight, and they have a lot of infrastructure that I certainly didn’t have during my time. So that's a comfort to me. Maybe I'm just more cynical, because I know what the setbacks look like, how long everything took to be able to get here. That's what I worry about. And I try to vocalize it amongst Asian American, Native Hawaiian, Pacific Islander audiences. I want to make sure that people understand we've got to protect the gains that we've been able to make, and that we're not in a period of advance, like we were just five years ago. We’re in a period of potentially rapid retreat.

At TAAF, we launched a campaign last year called Asian+American, and the whole idea was replacing the hyphen with a plus sign, and saying that we can be fully both. What does it mean to you to be Asian American? What does that term signify to you?

The way I tried to articulate it in the book is––this happened for my kids and it happened for me when I was coming up to California [from Hawaii] at the age of 18––you're forced into thinking, what makes you Asian? Let's make a list. And then what makes you American? Let's make a list of that as if it's a plus and minus column. And what I love about what you all are doing with the “plus” thing is that it's all additive. It's all who we are. It's indispensable.

We're bringing something very unique to the conversation about what it means to be American. And then we also have a lot to say about what it means to liberate all Americans as well…I think that's partly what I'm trying to bring out in Water Mirror Echo. Taking it back to the formative laws around immigration and exclusion. Which takes us from the Chinese Exclusion Act all the way to the current ICE shootings in Minneapolis. And there's no reason to hide that, or to be apologetic about the fact that our liberation is caught up with the liberation of other people, and that we have a lot to say.

You can find Water Mirror Echo at all your favorite booksellers.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

.png)