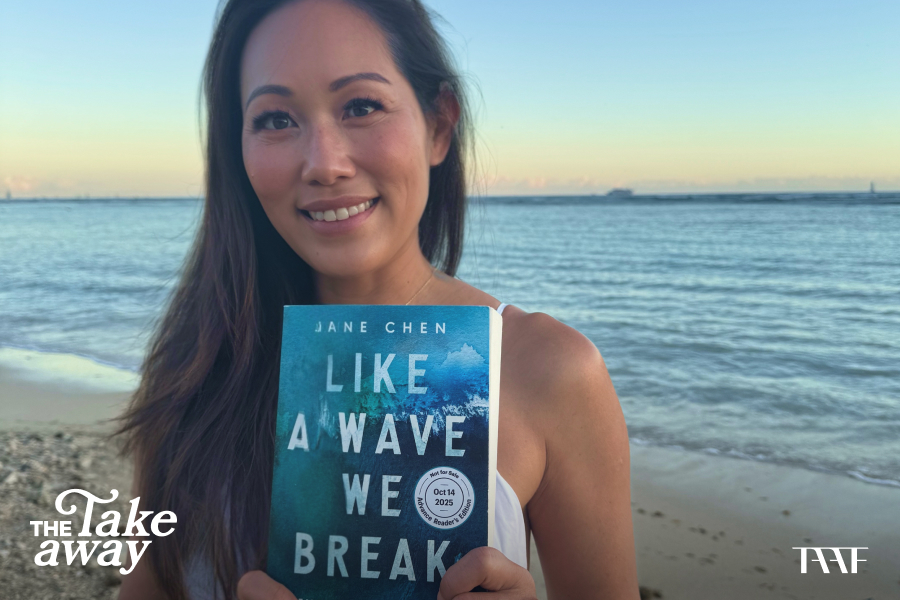

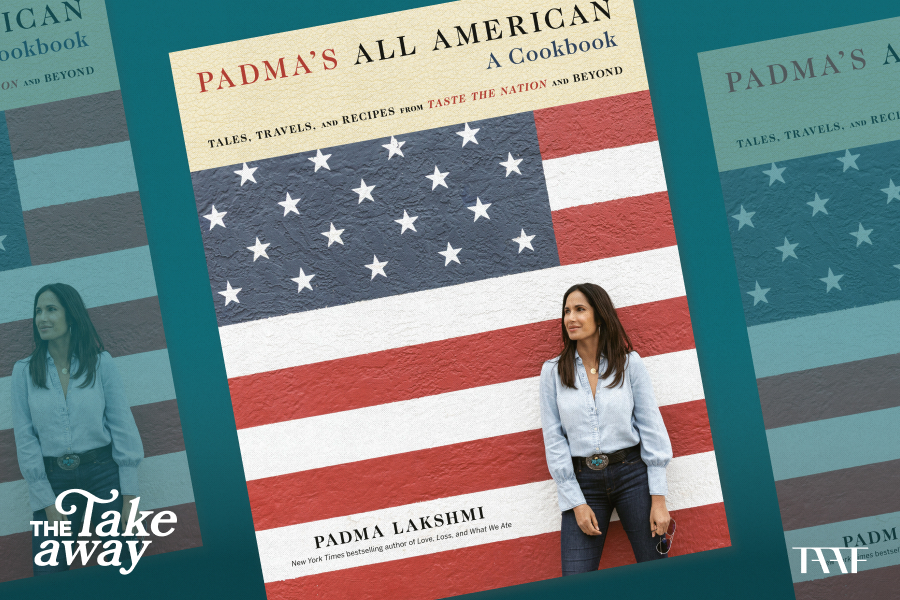

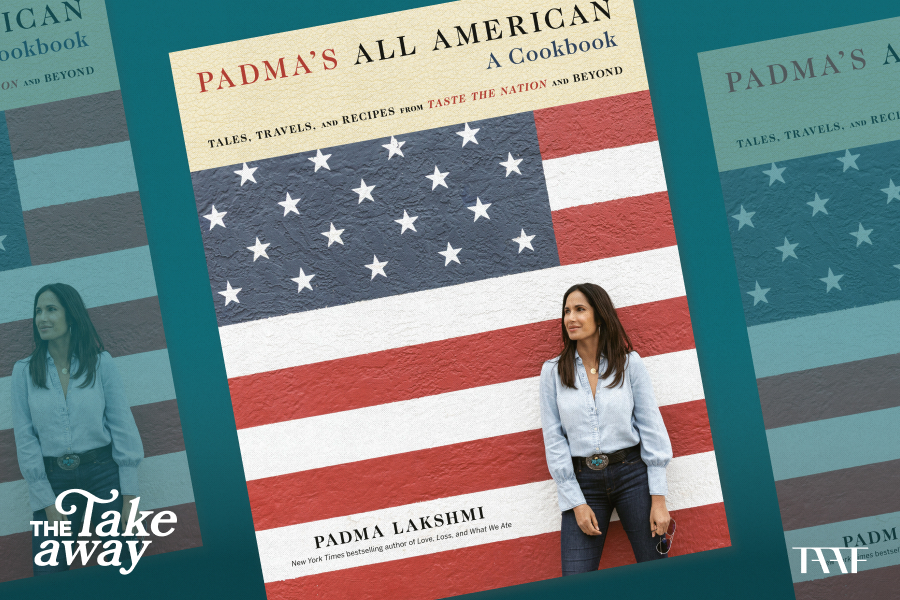

Padma Lakshmi's New Cookbook Explores How American Cuisine Is Rooted in Immigrant Communities

Padma Lakshmi’s new cookbook, Padma’s All American, is more than just a collection of recipes—it’s a thoughtful look at how the immigrant and Indigenous stories behind the dishes are really at the heart of American cuisine. I chatted with Padma about the timeliness of the book, and about how recipes can be made accessible while staying true to their origins.

Immigrant and Indigenous communities are central to Padma's All American. Many of the recipes come from Padma’s travels on Taste the Nation, her series on Hulu that explored food cultures across the country. Others come from Padma’s own South Indian heritage. At a time when “Americanness” is being questioned in the national discourse, and immigrant communities have found themselves targeted and vilified, I asked Padma what she hopes people will understand after reading her book.

“I'd like them to come away knowing that America is, first of all, a great place to eat all kinds of foods, because it's a microcosm of the world's cuisines, but more importantly, that our country is great and interesting and strong because of the contributions of generations of immigrants from all over the world,” she explained. “And through the writing, the profiles of people that I met on the road, I hope they see that. I hope they get curious and make the food, but I really hope it shows the beauty and diversity of this country.”

There are over 100 recipes in the cookbook, and they represent the fantastically rich diversity and complexity of flavors that this country’s cuisine has to offer. America’s food traditions are the result of waves of immigration, the legacy of slavery from West Africa, and the traditions held onto by resilient Indigenous cultures. From Cambodian Sach Ko Jakak (Kreung-Infused Beef Skewers) to Crab Fried Rice from the Gullah Geechee community, to a Lebanese, Ramadan-ready Fatteh Batinjan (Roasted Eggplant Layered with Chickpeas, Yogurt, and Pita), the recipes span a multitude of communities, and include meat and vegetarian recipes.

Each recipe includes some background on its origins, in addition to profiles of some of the people Padma met on her travels. One of the profiles is of Twila Cassadore, a forager who lives on the Apache San Carlos reservation. I asked Padma about the day she spent with Twila, and what she found especially moving about her story.

“We made a meal on an open fire with just the things found in the desert. And I remember thinking, wow, the Sonoran Desert is so beautiful, but if I was left here alone, I would freeze and starve within 48 hours!” With Twila’s expert guidance, they foraged for wild onions, ate gloscho (pack rat, which Padma assured me was delicious), harvested cactus and seasoned it with sumac that had been picked and dried, and made a salad of barrel fruit. “It was kind of a revelation to me, because we're struggling, as a planet, with a lot of environmental factors and risks. And in this country, we’ve pushed Indigenous people to the margins…and they actually hold knowledge that everyone, and the planet, can benefit from. I always knew that intellectually, but after spending the day with her, I understood it on a visceral level.”

Fans of Taste the Nation will recognize many of the stories and dishes featured in the book. But what’s also interesting to see are some of the adaptations, where Padma has put her own spin on a recipe. One example of this is the Blackened Corn with Suya Spice. In the episode of Taste the Nation where Padma visits the Nigerian community in Houston, actress and comedian Yvonne Orji introduces us to a spice, suya, which is used in a goat dish on the show. As there were already meat skewers and a Nigerian goat recipe planned for the book, Padma thought about combining suya with a dish she loved from her childhood. I asked her about her process in figuring out how to adapt this and other recipes.

“It was a difficult and tricky thing. I wanted to be sensitive to the people from the community that the recipe came from—to retain the essence of what made people from that community love that dish. I love the suya spice, and wanted to use this spice as a masala. I always grew up eating that blackened corn as a child, so that's how that was born. And there are a lot of Indians in Nigeria––not that that makes it okay or not okay––but I just felt like that made sense."

These types of culinary adaptations are actually in keeping with the experiences of so many immigrant home cooks, who have often had to recreate their traditional dishes in America with available ingredients. I asked if this process of adaptation was, in a way, a natural type of fusion.

“I think fusion has had a bad name since the 80s, because you wind up with things like tandoori chicken pizza. I do think there's a way to do fusion right,” Padma explains. “If you have to make substitutions because certain ingredients aren't available, you want to use ingredients that are available where you're cooking them. In the Desert Chicken, I use chile tepin, because that is the only chile pepper that's indigenous to North America. And so that change made sense there. But I also wanted it to be more accessible for people who are outside the community, and may not be familiar with those foods or those ingredients, to make it and enjoy it with their family, too.”

Throughout this cookbook, the deep love and respect for the communities from where the dishes originated is evident. And as people try these recipes they will, hopefully, learn something new about the people and stories behind the food we eat as well. Padma’s All American is out now.

.png)