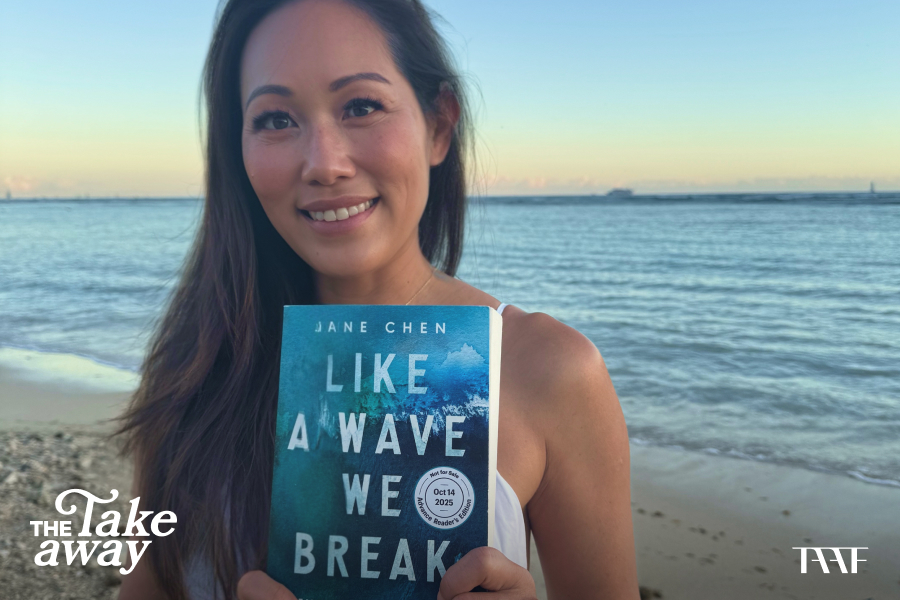

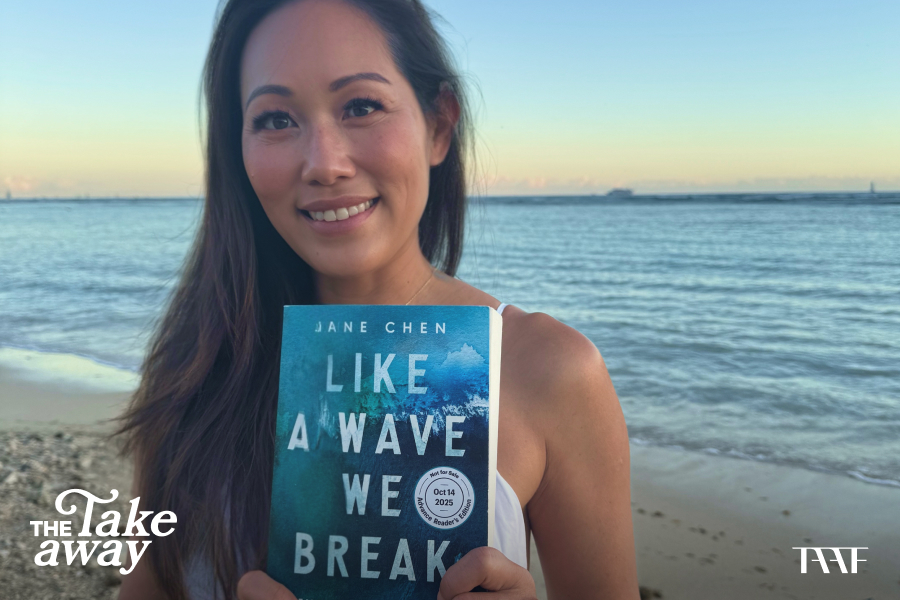

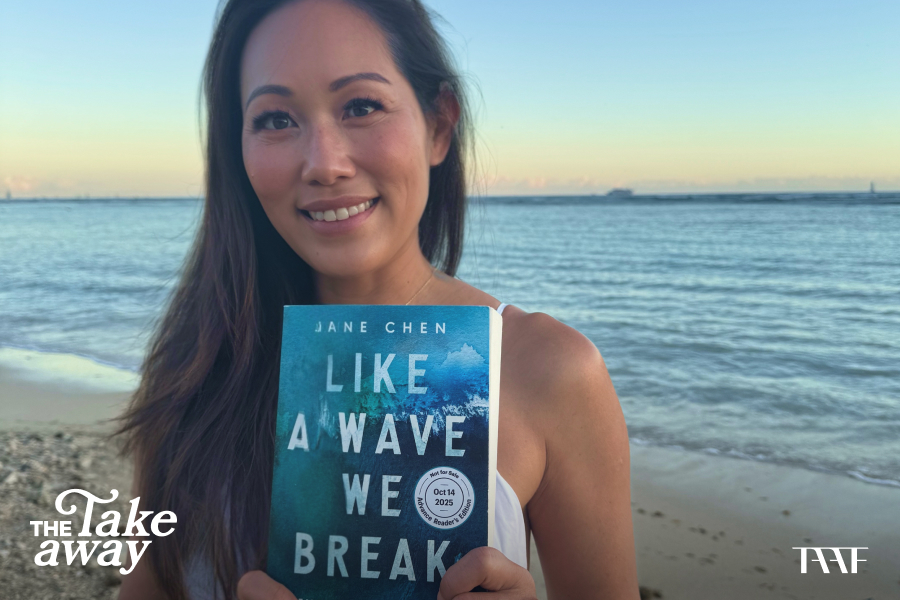

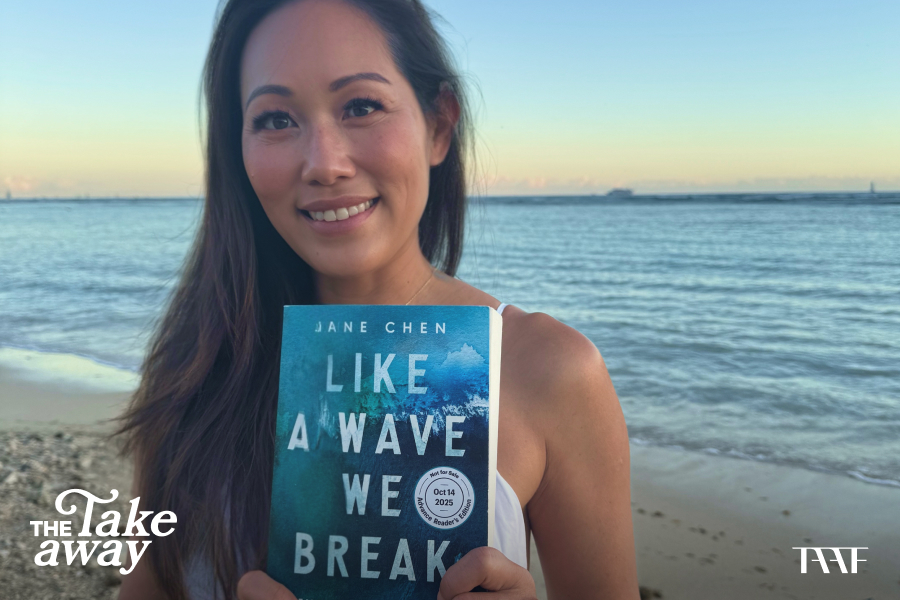

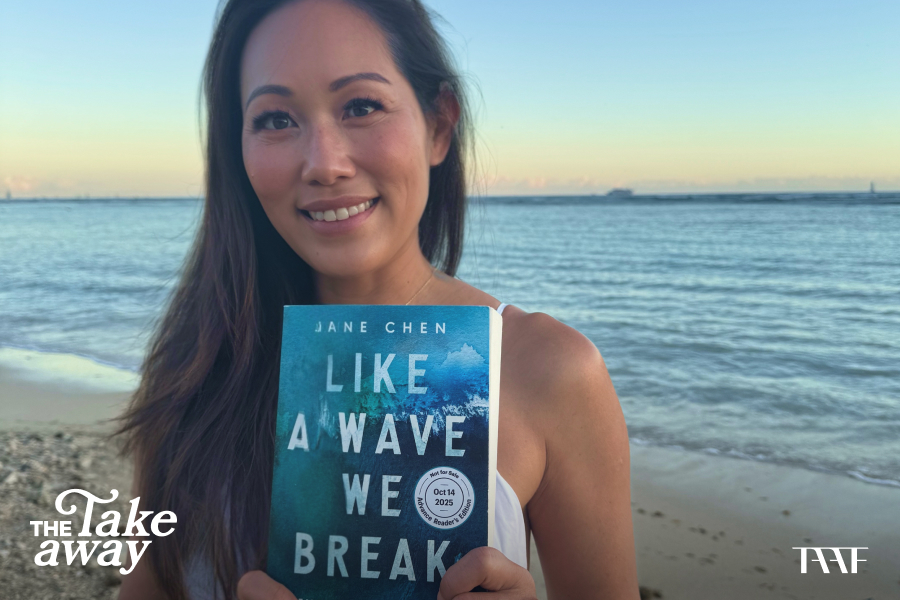

In a Powerful New Memoir, Jane Marie Chen Tackles AAPI Mental Health, Generational Trauma, and Her Journey To Healing

Inventor and entrepreneur Jane Marie Chen rose to prominence as the CEO and co-founder of Embrace, a groundbreaking, affordable infant incubator that has reached over a million of the most vulnerable babies.

On the surface she was the story of success, receiving numerous accolades on the world stage. But when the collapse of her company left her on the edge of a breakdown, Jane embarked on a healing journey that addressed deep, unresolved trauma. In her new memoir, Like a Wave We Break, we’re taken on a raw and emotional journey, as Jane does everything in her power to uncover truths about herself and her childhood, ultimately leading to a newfound understanding of self-worth and resilience. I chatted with Jane about the book, mental health issues in the AAPI community, and her drive to help those who are struggling.

In Like a Wave We Break, we not only get the fascinating story of how you built Embrace, but also the story of coming to terms with and overcoming trauma from your childhood. You speak very openly and candidly about corporal punishment and the abuse you endured as a child. What made you want to share this story?

I think it's a couple of things. I spent 10 years building Embrace, and I poured my whole life into it. When that came crumbling down, I went on this healing journey, and that's when I started to connect the dots—that it was my feeling so powerless throughout my childhood that motivated me to want to help the most powerless people. But the shadow side of that was just extreme burnout, and getting to the point where 10 years in, I had a mental breakdown. As I went on this healing journey, I came out the other side and really wanted to share this story of finding healing and self-compassion with anyone else who has struggled with this—especially in the Asian community, because these stories are often silenced and it's so normalized in our culture. The other thing that really tipped me over the edge in terms of having to share this was about five years ago, someone that I grew up with took his own life. And he was also a first generation Asian American. There was a lot of violence in their home. They grew up just down the street from me. And it shook me to my core, and I realized that when I'm silent, I'm complicit, and I'm perpetuating the cycles of abuse, and both I and we as a community have to start talking more openly about this.

There's one chapter in particular which is so chilling because you're with your friend in middle school, who is a child of Vietnamese immigrants, and you're talking about each dad's “weapon of choice” for beatings. What effect do you think the commonality of this experience has on AAPI youth—on whole generations?

I think other than that conversation, I never talked about it with my friends. I didn't talk about it with my sisters. It was something we swept under the rug. And I did not know how much that impacted me on so many levels until I understood the neuroscience of trauma. Whether it's abuse or neglect, it's not just something that stays in your past. Childhood trauma rewires your brain and your nervous system. It's how you bring that past into your present, and it affects everything—our self esteem, the way we see ourselves, the way we relate to others, the way we build our companies. I think there are a lot of explicit mental health issues in the Asian community, and also a lack of willingness to seek help for that, because it's so normalized. And you see that in the mental health statistics. But also, there is this pervasive sense of “not enoughness” that I see in the Asian American community. No matter what you do, no matter how good your grades are, what you accomplish professionally, there's still this belief that “I'm not enough.” And so we don't have this inner sense of self and confidence. And that leads to things like depression and suicide, like the string of suicides that happened in Palo Alto a number of years ago in the Asian American community.

For Asian American youth, I really believe a lot of it stems from this and from the lack of safety in talking about these issues. When something is so normalized in our cultures, we don’t even stop to think that there’s something wrong with the situation. It took me many years to realize how much of my life was me being in fight-or-flight. It's only in the last couple of years that I've come to see that resilience is actually slowing down, and being kind to ourselves and having that self compassion and that inner sense of worthiness.

You acknowledge in the book that you have a level of privilege where you got to seek therapy or try different techniques that not everyone might have as options. What do you think people from these immigrant communities can do to get healing?

I think there are a number of really great free resources out there. There are meditation retreats that are free of cost, and I'm actually preparing a page on my website to point people to different books and webinars. I think the first step is really awareness. That's what this book is about. And once people are aware, then it's taking the steps to go down that healing journey. And I think that there is no one size fits all—I was so lucky that I got to try all these things and I share some of the most effective tools. I'm preparing a number of free resources that people can download as well to practice these tools on themselves.

That's great. You also address generational trauma, and while it doesn't excuse the abuse, it's helpful to understand how these cycles are perpetuated for many immigrant families. Do you feel like the cycle can be broken?

I do. I really do. I think it really comes down to awareness and acknowledgement, and being able to safely talk about these things. And I say that because I've seen it in my own family, as I started to confront my parents about what happened. For years, my mom would say to me, "Well, this was cultural, everyone got beaten up. This is just what happens." And I think two things have happened. One is just continuing to have those conversations and not be shut down, but continuing to confront this with my mother, especially. And I mention in the epilogue of the book that Taiwan is the fourth country in Asia to be passing legislation to ban corporal punishment in homes, which is mind blowing to me because even a couple years ago, that wouldn't have been the case. It’s thanks to the science and research.

The Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACE) study, which I talk about, is a landmark study done by the CDC and Kaiser Permanente. They surveyed 17,000 adults in America—most were college educated and middle income—and they found that 66% had reported at least one significant adverse childhood event. Those who have higher ACE scores are much more likely to develop heart disease, diabetes, cancer—this is directly linked to our health outcomes. Someone with an ACE score of 4 or more is 12 times more likely to attempt suicide. As societies and governments and individuals start to understand the effects and also start to understand the science, they're opening up to new ways of being. My mom is really starting to acknowledge her own pain she had grown up with, but just us being able to have open conversations about this is huge. And I absolutely think that with that level of awareness and openness, you can break these cycles.

How does your family feel about the book?

It's very emotional, as you can imagine. It's such a vulnerable story, but the thing I feel so grateful for is my mom said, "If this helped you in your healing process, then I support it." Writing a book is very healing in that it forces you to really go into the details and the visceral experience of what happened. It forced me to zoom out to this 30,000 foot level and see how my whole story was connected. My family, my family history, all of the stuff about the history of Taiwan that I didn’t know until I wrote the book. Taiwan was under martial law for 38 years. There was so much political oppression, and silencing of people, and hundreds of thousands of innocent people lost their lives in that period. And everyone was afraid to talk about it. Many of us as immigrant families are fleeing persecution or political oppression or war. And that trickles into family systems. And that's what I've really started to understand.

When I first set out to write this book, my intention was to write about every person with love and respect and to tell the truth. And to balance those two things has been challenging, given that I'm talking about some difficult topics, I'm talking about abuse and trauma. But I think I do have very deep compassion for my parents. And I do forgive them. In the process of my healing, I've also learned what boundaries are for myself, and the kind of behaviors that I don't want to be around.

Like a Wave We Break comes out on October 14th. What's next for you? Are you still involved with Embrace?

I stepped down in May. We reached a million babies this year, and I hired a new CEO. We have a team that's taking the mission forward, and that feels amazing. It's been 17 years since we started the company. We set the goal of reaching a million babies as Stanford students. To be able to reach that and then pass the baton has been such a beautiful experience. The two things I'm doing with my career from here on are corporate leadership coaching, and working directly with kids who have trauma. That's where my heart is driving me. I feel so privileged to learn from the teachers I have learned from, and my goal is to be able to pass that knowledge on to everyone else.

You can preorder Like a Wave We Break here. You can also see Jane Chen in conversation on one of her upcoming book tour dates or at this virtual fireside chat on October 13th!

.png)