Asian+American Stories: Liz Kleinrock on Her Identity as a Transracial Adoptee

As part of our Asian+American campaign, we're featuring personal stories that celebrate pride in being both Asian and American. Liz Kleinrock is the Director of Diversity, Equity, Inclusion and Belonging at the Lowell School in Washington, DC. She’s also an anti-bias and anti-racist consultant and facilitator, as well as an author. Liz spoke with us about being a transracial adoptee, and how that has informed her identity.

As a transracial adoptee, your Asian+American story has added layers of complexity. Could you tell me about your childhood and how you saw yourself?

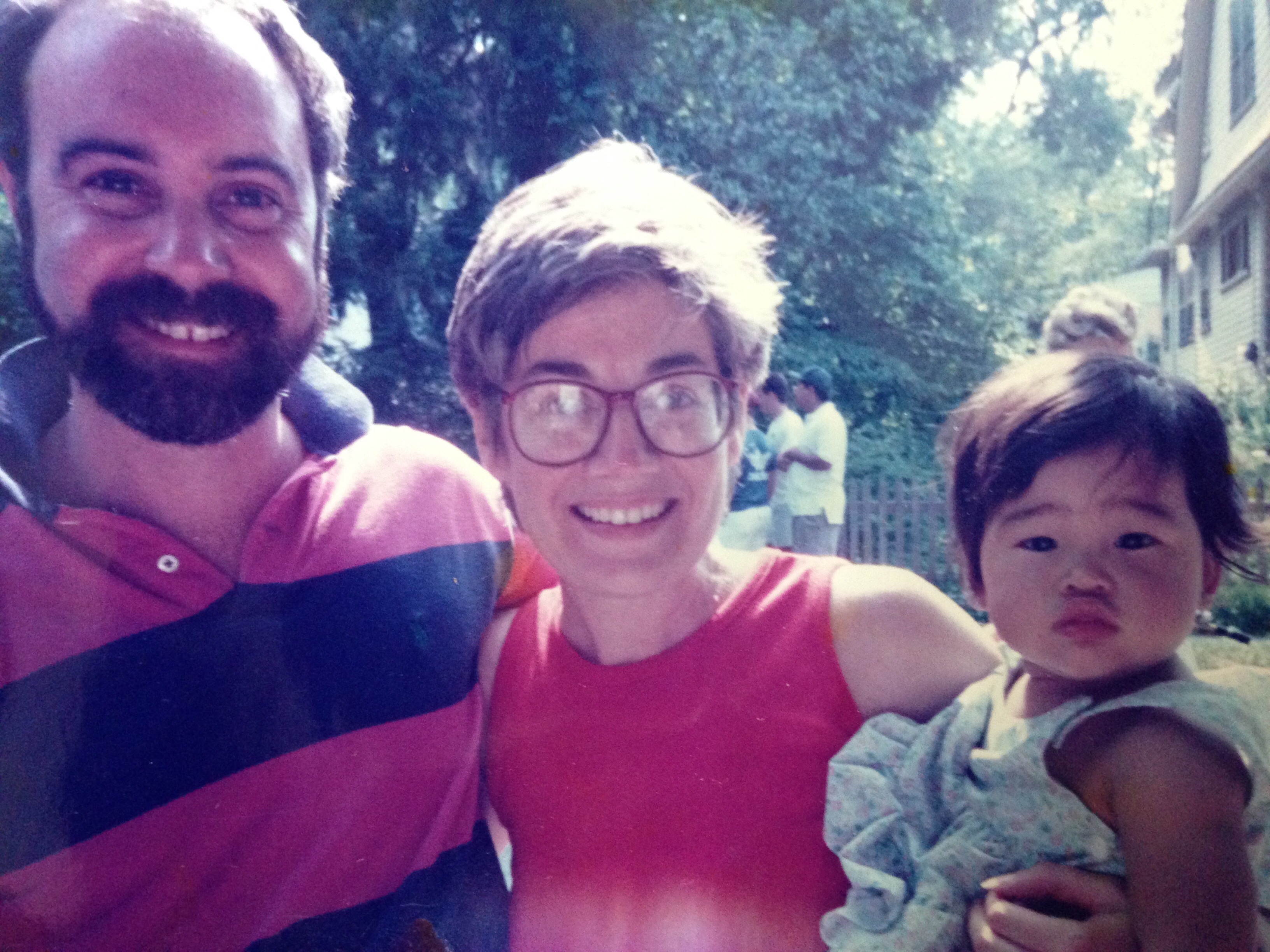

I was born in Iksan, South Korea, about 1½ - 2 hours south of Seoul. It's a pretty rural area. I was adopted into a white, Jewish family here in Washington, DC, when I was 5 months old. Growing up, and to this day, I'm still the only person of color in my immediate and extended family. I grew up in a very white neighborhood of a very historically black city, and the only other Korean people I saw in my neighborhood was the family that owned the dry cleaners nearby, and then there were a fairly small number of other Korean and East Asian students in my class.

I think because of the lack of mirrors growing up, I definitely connected in a stronger way with my Jewish identity. I very much considered myself ethnically and culturally Jewish. My family keeps kosher, my parents go to minyan every Saturday morning. And so that was very much the world that I was immersed in as a kid. It really wasn't until college that I started taking Korean language classes, and I had more Korean friends. I went to Korea for the first time since being born there. So my journey started a lot later in life with exploring what it means to be Asian, what it means to be Asian American. It was also something that was very self-driven. I know that if I hadn't had that desire to explore that, it really wouldn't have happened.

So your parents didn't really approach that discussion with you growing up?

No. My parents and I have a really strong, really great relationship, and I am very aware—and they have also spoken to me about this—that the perspective at that time when they were becoming parents was that we don't talk about race, we don't talk about those differences. We're very race-evasive—we just treat everybody the same. Which is a lovely aspiration but unfortunately, as we know, that’s not really how the world works. And that just means that—at least for me as a kid—you don't really have a lot of the context or language to be able to talk about who you are, or even the skill set to answer questions when people ask you intrusive things about where you're from, or why you don't look like the rest of the people in your family.

I’ve always identified as Asian and I’ve always identified as Korean too. I think for the most part, my parents did a very good job of making sure that I knew where I came from. There were a very limited number of books out there—The Korean Cinderella, which is written by a white person, was the only thing that I had, but I still felt an affinity towards that book as a kid. And there was the Yellow Power Ranger, Trini, even though she's Vietnamese, and Mulan, even though she's Chinese—I was grasping for any sense of familiarity or representation in a positive way.

Did you feel caught between cultures, or was it more that people had different perceptions of you?

It's a good question, and I often wonder if it was something that I internalized and maybe projected onto other people…but there's a lot to my identity that you wouldn't know without ever having a conversation with me. Oftentimes in Asian spaces, there are assumptions that just because you present in a certain way, that means that there must be certain commonalities without actually knowing for sure. I remember one of the first AAPI affinity spaces I was in––it was really powerful just to look out and see so many people that mirrored my own racial and ethnic identity. At the same time, when people started talking about family and culture and experience, I could not have had a more different experience to some of the things that they were sharing. And sometimes, especially when I was younger, I would have this subconscious anxiety about being “found out,” that people would think that I wasn't Asian enough or the right kind of Asian. I've done a lot of therapy and a lot of self work—working through multiple layers of impostor syndrome—and I certainly don't feel that way anymore. But it's taken a long time to get there.

Are you involved with Korean adoptee organizations, and with other transracial adoptees?

I've done two different programs in Korea for adoptees. The Overseas Korean Foundation, OKF, did one that allowed me to go back to Korea in 2022. I also did one the following summer with ASIA Families, which is based here in the D.C area. They do Korean culture camp for younger Korean adoptees, there’s programming for adoptive parents, and ways for adult adoptees to stay in contact. Here in the United States, there’s KAAN, the Korean Adoptee Adoptive Family Network, and they do a conference every year—I presented at that last year. And in Korea, a friend of mine and I presented at IKAA, which is the International Korean Adoptee Association. There are a lot of organizations out there. I think with social media, it's become easier to connect with other people. And I have my Korean adoptee text chain. Having those connections with people who just understand all the different layers of complexity and understand when people make comments that are really activating for you…it’s a great feeling when you don't have to explain that part of yourself.

Have you met other Korean adoptees who are Jewish?

Oh, yeah. There's actually an organization called LUNAR, which is an Asian and Jewish organization. They have a fellowship, they have a couple of chapters around the country as well. There are folks who I'm really glad are very visible in the Jewish community, Rabbi Angela Buchdahl comes to mind immediately. She is Korean American and leads Central Synagogue, which is the largest reform synagogue in New York. She's amazing, she's an icon.

You also write children's books. Are they about the topic of identity?

Yes. I write kids’ books that I wish I had when I was growing up. The first one that came out is called Come and Join Us. It’s a look at holidays that are happening all year long. I love that one very much. The second one was co-written with my friend Joanna Ho. She writes a lot about different Asian American themes, but Eyes that Weave the World’s Wonders is very specifically about my adoption story. And also recognizing that my adoption journey is different from a lot of adoptees’ journeys—we are certainly not a monolith. And the most recent one is a middle grade nonfiction that I coauthored with my friend Caroline Kusin Pritchard, called What Jewish Looks Like. It explores and celebrates the diversity within the Jewish community.

Is there anything you wish you could say to your younger self about being Asian American?

You're not alone—you're enough. You don’t owe anyone receipts. You just are who you are, and if they have a problem with it, that's a “them” problem. It's actually not a “you" problem. Something one of my therapists told me about battling feelings of imposter syndrome was how important it is to put yourself out there because when you do, you increase that visibility for people who share parts of your identity. The generational impact of that is that you get to actually help combat and lessen imposter syndrome throughout the generations. How beautiful and important is that?

What does being Asian+American mean to you?

I think being Asian+American is something to be really proud of. There are so many different stories that collectively create this collage of who we are as a community. And I think particularly being a Korean American adoptee, I feel like I am and we are the epitome of what it means to be Asian and American. We are born of Asia, we are part of this massive diaspora, and we are also in the United States as a result of policies and practices that came about from U.S. intervention and occupation in Korea. What could be more Asian American than us, you know?

Learn more about our Asian+American campaign and how you can get involved here.

.png)